MARNIE WEBER

WHEN ROSES BLOOM

JANUARY 25 – MARCH 1, 2025

The mind grows rings

by Kyla McDonald

Flowers and their organic sequence of conception, growth, and decay are often understood as a metaphor for the days and phases of human life. The beautiful and nubile young woman forever reflected in the image of a blooming rose. A spoiling flower that is slowly surrendering itself to rot reminds us of the certainty of time passing – an image beautifully appropriated by the seventeenth century Dutch genre of vanitas painting, which set out to remind viewers of death’s inevitability.

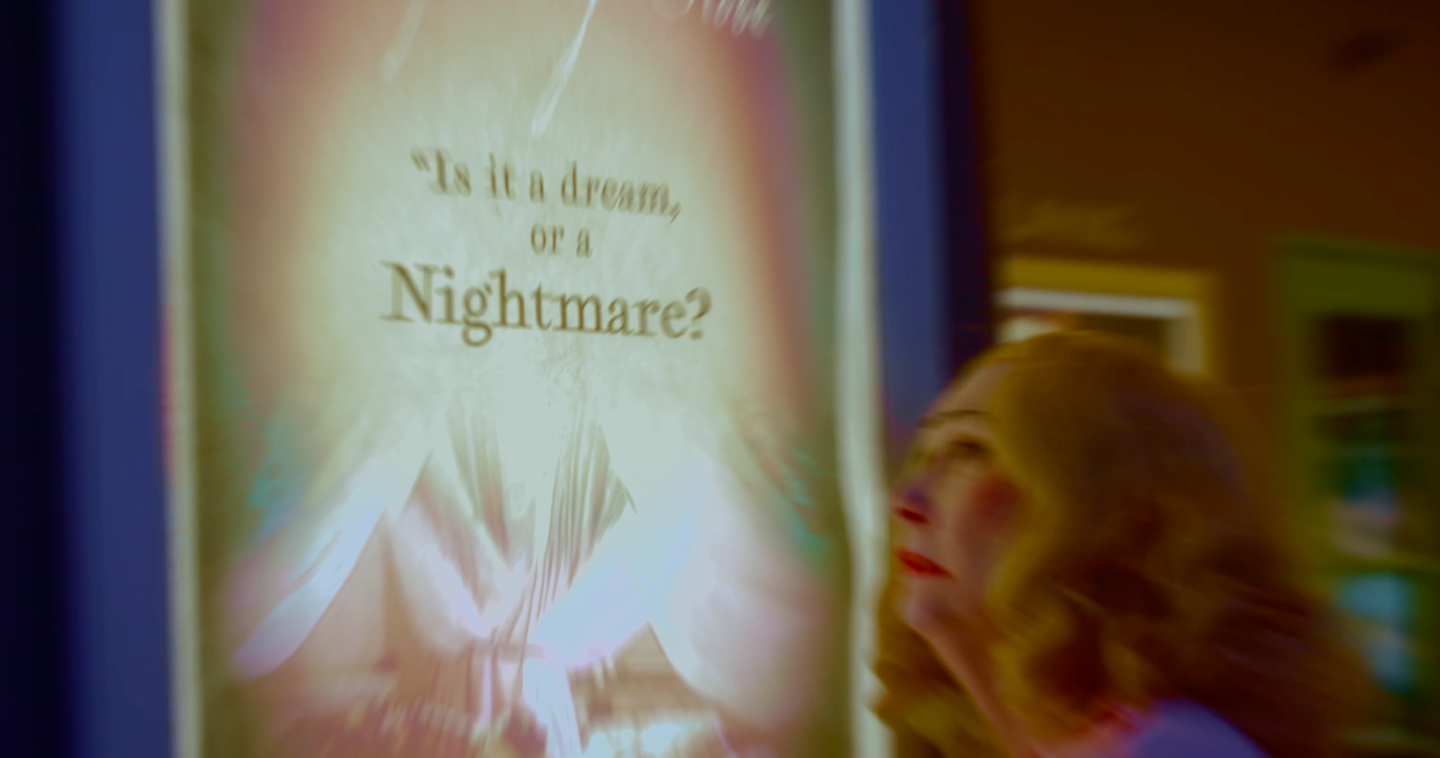

Marnie Weber’s film House of the Whispering Rose (2025) opens with the camera panning across a pink rose bush. It cuts in and out of close-up images of different flower-heads, each in varying degrees of blossom and decay. This scene, a kind of vanitas, sets the stage for a work that observes the particulars of aging that are bestowed upon women who have reached the so-called purgatory of later life. Rose Bloom (Weber’s protagonist) is an aging Hollywood star from a bygone era. Her girlish, pink ruffled dresses, clownish make-up, and ringleted hair strike a particularly tragic, if not comedic, chord – a sign of her wish to remain represented in the moment she was still desirable (and a nod to classic 1962 movie What Ever Happened To Baby Jane?). Rose wanders the rooms of her vast estate – itself a relic of former grandeur – in a kind of half-conscious fever-dream. She is an archetype of an aging and washed-up star. Used and discarded by the same system that once promised her she would never be forgotten, she appears to have been slowly driven mad by her irrelevancy and loneliness. Those echoes of madness resound in the ghosts, living furniture, and strange characters that populate her world.

Rose appears throughout the film as both her older and younger self (played by Weber’s own daughter). The two versions wear the same clothes, and the scenes where each Rose performs similar actions – looking in a mirror, dancing, celebrating a birthday – are interwoven with each other, disrupting temporal logic. There is, in fact, no discernible feeling of ‘real’ time here. In a sense Rose appears to be in an endless moment of being – a phrase used by Virginia Woolf to describe the instances when an individual experiences a deeper connection with their existence and the universe, and those which are outside the ordinary and mundane times of consciousness that dominate our day-to-day lives.

Weber’s exploration of, and use of time in this work finds alignment in the ways that feminist theory has sought to rethink the rubric of time and temporality. The conventional, linear model of time is understood as a construct that perpetuates normative and patriarchal structures that advocate for continual progress, productivity, and control. This model acts directly against marginalized groups whose experience of time is often outside of those phallocentric and mechanized temporal logics. The forgotten aging woman, no longer of value economically, sexually, intellectually – perceived to be going mad – being one such example. A feminist understanding of time is more fluid, non-linear, and cyclical allowing for a more diverse range of experiences and narratives to be reclaimed and hold weight. As normative temporal logics are refuted, so too is the idea that time is spatialized. Such ideas seek to open up possibilities of touching across, or collapsing, time in order to offer alternative frameworks for being.

Similarly, Weber’s suspension of linear time in House of the Whispering Rose allows her to reclaim Rose’s trajectory. Rose’s moment of being is populated with allusions to renewal and rebirth. While the motif of the withering rose does denote decline, flowers lifecycles repeat, nurturing continual regeneration and transformation. The Wiccan characters that Rose envisions carry similar symbolism – for example, the bunny represents birth and fertility, the owl magic and wisdom, and moon represents the cyclical patterns of life, death, and rebirth. For Woolf, moments of being offered a space for revelation and possibilities for transcendence. As she writes in The Waves (1931), ‘the mind grows rings; the identity becomes robust; the pain is absorbed in growth.’ This is not an ending, Weber seems to be telling us, but rather a renewal – a moment of beautiful metamorphosis.

***

Kyla McDonald is a curator, writer, and art historian based in Berlin. Her research encompasses enquiries into overlooked narratives in art history, artist-women, intergenerational dialogue, and the practice of queer, feminist, and de-colonial methodologies. She recently completed her PhD in feminist art history on the work of Hilma af Klint, Lee Lozano, and Betye Saar. She has held curatorial roles at Bonner Kunstverein; Glasgow Sculpture Studios; Tate Modern; and Tate Liverpool.

Marnie Weber lives and works in Los Angeles. For over four decades the artist has worked with music, performance, collage, film, painting, and sculpture to create uncanny worlds that evoke the genres of fairytales, folklore, and mythology, but which come wholly from Weber’s own vivid imagination. Populated by witches, monsters, clowns, animals, and strong female characters, the artist’s surreal fictions recount journeys of transformation and self-discovery, exploring the complexity of the subconscious. Weber’s work is characterized by its deliberate home-made aesthetic, its careful suspension between darkness and subtle humor, and her long-standing interest in the reclamation of female power.